CERVICAL CANCER

The cervix is a cylinder-shaped neck of tissue that connects the vagina and uterus. Located at the lowermost portion of the uterus, the cervix is composed primarily of fibromuscular tissue. There are two main portions of the cervix:

• The part of the cervix that can be seen from inside the vagina during a gynecologic examination is known as the ectocervix. An opening in the center of the ectocervix, known as the external os, opens to allow passage between the uterus and vagina.

• The endocervix, or endocervical canal, is a tunnel through the cervix, from the external os into the uterus.

The overlapping border between the endocervix and ectocervix is called the transformation zone. The cervix produces cervical mucus that changes in consistency during the menstrual cycle to prevent or promote pregnancy.

During childbirth, the cervix dilates widely to allow the baby to pass through. During menstruation, the cervix opens a small amount to permit passage of menstrual flow.

The skin like cells of the ectocervix can become cancerous, leading to a squamous cell cervical cancer. The glandular cells of the endocervix can also become cancerous, leading to an adenocarcinoma of the cervix. The area where cervical cells are most likely to become cancerous is the transformation zone. It is the area just around the opening of the cervix that leads on to the endocervical canal. The endocervical canal is the narrow passageway that runs up from the cervix into the womb.

About 90% of cervical cancer cases are squamous cell carcinomas, 10% are adenocarcinoma, and a small number are other types. Diagnosis is typically by cervical screening followed by a biopsy. Medical imaging is then done to determine whether or not the cancer has spread.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection appears to be involved in the development of more than 90% of cases; most people who have had HPV infections, however, do not develop cervical cancer. Other risk factors include smoking, a weak immune system, birth control pills, starting sex at a young age, and having many sexual partners, but these are less important.

Worldwide, cervical cancer is both the fourth-most common cause of cancer and the fourth-most common cause of death from cancer in women. In India, the number of people with cervical cancer is rising, but overall the age-adjusted rates are decreasing. Usage of condoms in the female population has improved the survival of women with cancers of the cervix

Signs and symptoms

Women with early cervical cancers and pre-cancers usually have no symptoms. Symptoms often do not begin until the cancer becomes invasive and grows into nearby tissue. When this happens, the most common symptoms are:

• Abnormal vaginal bleeding, such as bleeding after vaginal sex, bleeding after menopause, bleeding and spotting between periods, and having (menstrual) periods that are longer or heavier than usual. Bleeding after douching or after a pelvic exam may also occur.

• An unusual discharge from the vagina - the discharge may contain some blood and may occur between your periods or after menopause.

• Pain during sex.

These signs and symptoms can also be caused by conditions other than cervical cancer. For example, an infection can cause pain or bleeding. Symptoms of advanced cervical cancer may include: loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, pelvic pain, back pain, leg pain, swollen legs, heavy vaginal bleeding, bone fractures, and (rarely) leakage of urine or feces from the vagina. Bleeding after douching or after a pelvic exam is a common symptom of cervical cancer.

Causes

Causes and risk factors for cervical cancer include human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, having many sexual partners, smoking, taking birth control pills, and engaging in early sexual contact. Not all of the causes of cervical cancer are known, however, and several other contributing factors have been implicated

HPV, or human papillomavirus, is a virus that infects the skin and the cells lining body cavities. It is spread through close skin-to-skin contact, often during sexual activity. It is a very common infection which usually causes no symptoms at all.

HPV infections are usually on the fingers, hands, mouth and genitals. For most people, the body will clear the infection on its own and they will never know they had it. But in some people the infection will stay around for a long time and become persistent.

There are hundreds of different types of HPV. Most are harmless. But around 13 types of HPV can cause cancer. These are called ‘high-risk’ types. People with persistent infections with ‘high-risk’ HPV types are those who are most likely to go on to develop cancer. Normally, HPV infections start in the deepest layers of the skin. During an infection, HPV causes skin cells to divide more than usual. New virus particles are then made inside these cells.

This fast skin growth can cause warts, including genital warts, to develop, but often it doesn’t cause any symptoms at all. The types of HPV that cause warts are not the same types that cause cancer. In some people with persistent ‘high-risk’ HPV infections, the virus damages the cells’ DNA and causes cells to start dividing and growing out of control. This can lead to cancer. HPV can cause cancers in other genital areas, like the vagina, vulva, penis, and anus, as well as some types of cancer of the mouth and throat. As with cervical HPV infections, using a condom can reduce the risk of spreading HPV. Other factors can increase the risk of HPV-related cancers.

Cigarette smoking, both active and passive, increases the risk of cervical cancer. Among HPV-infected women, current and former smokers have roughly two to three times the incidence of invasive cancer. Passive smoking is also associated with increased risk, but to a lesser extent.

Smoking has also been linked to the development of cervical cancer. Smoking can increase the risk in women a few different ways, which can be by direct and indirect methods of inducing cervical cancer. A direct way of contracting this cancer is a smoker has a higher chance of CIN3 occurring which has the potential of forming cervical cancer. When CIN3 lesions lead to cancer, most of them have the assistance of the HPV virus, but that is not always the case, which is why it can be considered a direct link to cervical cancer. Heavy smoking and long-term smoking seem to have more of a risk of getting the CIN3 lesions than lighter smoking or not smoking at all. Although smoking has been linked to cervical cancer, it aids in the development of HPV which is the leading cause of this type of cancer. Also, not only does it aid in the development of HPV, but also if the woman is already HPV-positive, she is at an even greater likelihood of contracting cervical cancer.

Long-term use of oral contraceptives is associated with increased risk of cervical cancer. Women who have used oral contraceptives for 5 to 9 years have about three times the incidence of invasive cancer, and those who used them for 10 years or longer have about four times the risk.

Having many pregnancies is associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. Among HPV-infected women, those who have had seven or more full-term pregnancies have around four times the risk of cancer compared with women with no pregnancies, and two to three times the risk of women who have had one or two full-term pregnancies.

Diagnosis

Biopsy

The Pap smear can be used as a screening test, but is false negative in up to 50% of cases of cervical cancer. Confirmation of the diagnosis of cervical cancer or precancer requires a biopsy of the cervix. This is often done through colposcopy, a magnified visual inspection of the cervix aided by using a dilute acetic acid (e.g. vinegar) solution to highlight abnormal cells on the surface of the cervix. Medical devices used for biopsy of the cervix include punch forceps, SpiraBrush CX, SoftBiopsy, or Soft-ECC.

Colposcopic impression, the estimate of disease severity based on the visual inspection, forms part of the diagnosis.

Further diagnostic and treatment procedures are loop electrical excision procedure and conization, in which the inner lining of the cervix is removed to be examined pathologically. These are carried out if the biopsy confirms severe cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Often before the biopsy, the doctor asks for medical imaging to rule out other causes of woman’s symptoms. Imaging modalities such as ultrasound, CT scan and MRI have been used to look for alternating disease, spread of tumor and effect on adjacent structures. Typically, they appear as heterogeneous mass in the cervix.

Precancerous lesions

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, the potential precursor to cervical cancer, is often diagnosed on examination of cervical biopsies by a pathologist. For premalignant dysplastic changes, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grading is used.

The naming and histologic classification of cervical carcinoma precursor lesions has changed many times over the 20th century. The World Health Organization classification system was descriptive of the lesions, naming them mild, moderate, or severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ (CIS). The term, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) was developed to place emphasis on the spectrum of abnormality in these lesions, and to help standardise treatment. It classifies mild dysplasia as CIN1, moderate dysplasia as CIN2, and severe dysplasia and CIS as CIN3. More recently, CIN2 and CIN3 have been combined into CIN2/3. These results are what a pathologist might report from a biopsy.

These should not be confused with the Bethesda system terms for Pap smear (cytopathology) results. Among the Bethesda results: Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (LSIL) and High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (HSIL). An LSIL Pap may correspond to CIN1, and HSIL may correspond to CIN2 and CIN3, however they are results of different tests, and the Pap smear results need not match the histologic finding

Staging

Cervical cancer is staged by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system, which is based on clinical examination, rather than surgical findings. It allows only these diagnostic tests to be used in determining the stage: palpation, inspection, colposcopy, endocervical curettage, hysteroscopy, cystoscopy, proctoscopy, intravenous urography, and X-ray examination of the lungs and skeleton, and cervical conization.

Stage I

Stage I is carcinoma strictly confined to the cervix; extension to the uterine corpus should be disregarded. The diagnosis of both Stages IA1 and IA2 should be based on microscopic examination of removed tissue, preferably a cone, which must include the entire lesion.

• Stage IA: Invasive cancer identified only microscopically. Invasion is limited to measured stromal invasion with a maximum depth of 5 mm and no wider than 7 mm.

• Stage IA1: Stage IA1: Measured invasion of the stroma no greater than 3 mm in depth and no wider than 7 mm diameter.

• Stage IA2: Stage IA2: Measured invasion of stroma greater than 3 mm but no greater than 5 mm in depth and no wider than 7 mm in diameter.

• Stage IB: Stage IB: Clinical lesions confined to the cervix or preclinical lesions greater than Stage IA. All gross lesions even with superficial invasion are Stage IB cancers.

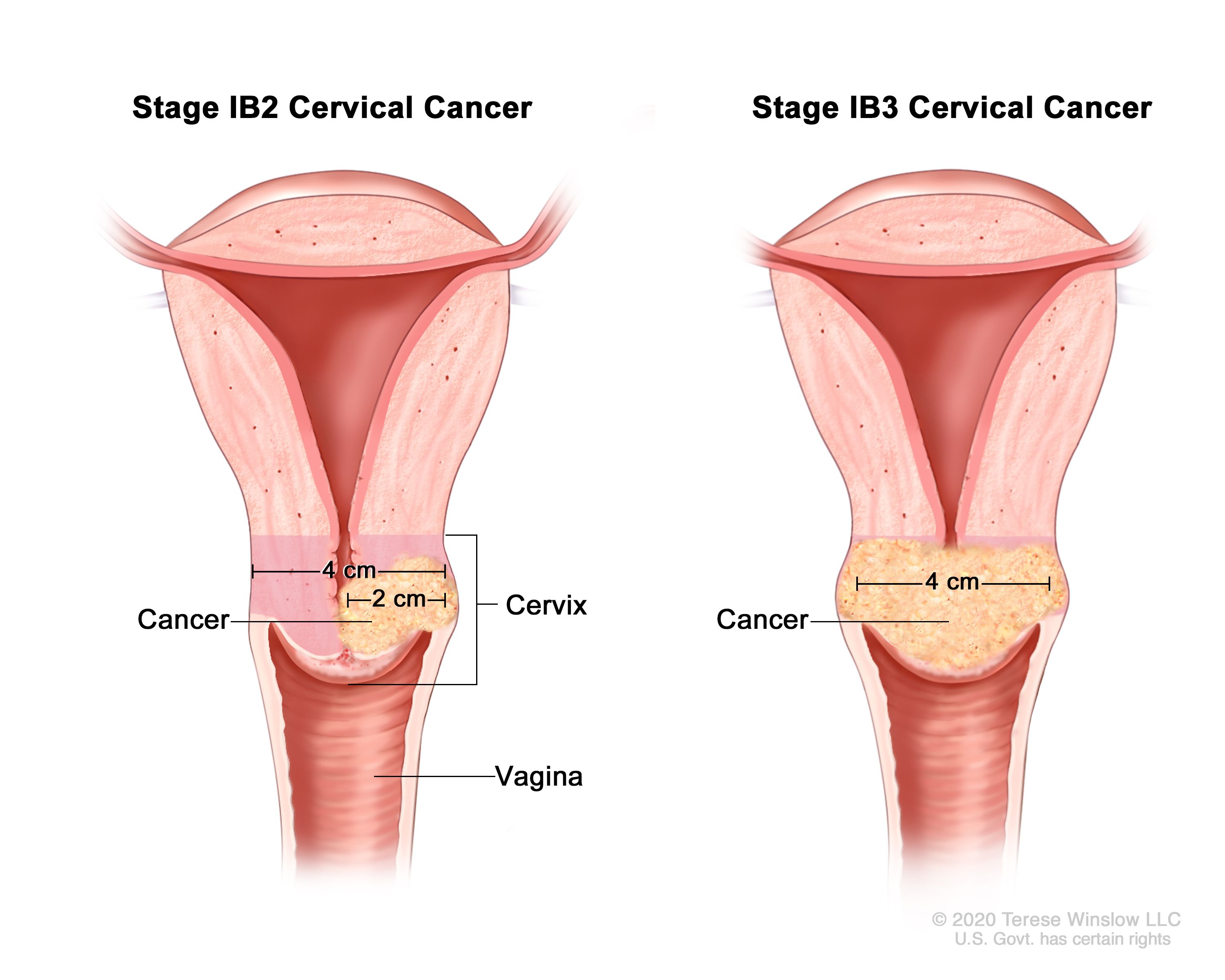

• Stage IB1: Stage IB1: Clinical lesions no greater than 4 cm in size.

• Stage IB2: Stage IB2: Clinical lesions greater than 4 cm in size.

Stage II

Stage II is carcinoma that extends beyond the cervix, but does not extend into the pelvic wall. The carcinoma involves the vagina, but not as far as the lower third.

• Stage IIA: No obvious parametrial involvement. Involvement of up to the upper two-thirds of the vagina.

• Stage IAB: Obvious parametrial involvement, but not into the pelvic sidewall.

Stage III

Stage III is carcinoma that has extended into the pelvic sidewall. On rectal examination, there is no cancer-free space between the tumour and the pelvic sidewall. The tumour involves the lower third of the vagina. All cases with hydronephrosis or a non-functioning kidney are Stage III cancers.

• Stage IIIA: No extension into the pelvic sidewall but involvement of the lower third of the vagina.

• Stage IIIB: Extension into the pelvic sidewall or hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney.

Stage IV

Stage IV is carcinoma that has extended beyond the true pelvis or has clinically involved the mucosa of the bladder and/or rectum.

• Stage IVA: Spread of the tumour into adjacent pelvic organs.

• Stage IVB: Spread to distant organs.

Screening

Cervical screening is the process of detecting and removing abnormal tissue or cells in the cervix before cervical cancer develops. By aiming to detect and treat cervical neoplasia early on, cervical screening aims at secondary prevention of cervical cancer.[2] Several screening methods for cervical cancer are the Pap test (also known as Pap smear or conventional cytology), liquid-based cytology, the HPV DNA testing and the visual inspection with acetic acid. Pap test and liquid-based cytology have been effective in diminishing incidence and mortality rates of cervical cancer in developed countries but not in developing countries.Prospective screening methods that can be used in low-resource areas in the developing countries are the HPV DNA testing and the visual inspection.

Cervical cancer is ranked as the most frequent cancer in women in India. India has a population of approximately 365.71 million women above 15 years of age, who are at risk of developing cervical cancer. The current estimates indicate approximately 132,000 new cases diagnosed and 74,000 deaths annually in India, accounting to nearly 1/3rd of the global cervical cancer deaths.Indian women face a 2.5% cumulative lifetime risk and 1.4% cumulative death risk from cervical cancer. At any given time, about 6.6% of women in the general population are estimated to harbor cervical HPV infection. HPV serotypes 16 and 18 account for nearly 76.7% of cervical cancer in India. Warts have been reported in 2–25% of sexually transmitted disease clinic attendees in India; however, there is no data on the burden of anogenital warts in the general community.

Surgery

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. A surgical oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancer using surgery. For cervical cancer that has not spread beyond the cervix, these procedures are often used:

• Conization is the use of the same procedure as a cone biopsy to remove all of the abnormal tissue. It can be used to remove microinvasive cervical cancer.

• LEEP is the use of an electrical current passed through a thin wire hook. The hook removes the tissue. It can be used to remove microinvasive cervical cancer.

• A hysterectomy is the removal of the uterus and cervix. Hysterectomy can be either a simple hysterectomy or a radical hysterectomy. A simple hysterectomy is the removal of the uterus and cervix. A radical hysterectomy is the removal of the uterus, cervix, upper vagina, and the tissue around the cervix. In addition, a radical hysterectomy includes an extensive pelvic lymph node dissection, which means the removal of the lymph nodes.

• If needed, surgery may include a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. It is removal of both fallopian tubes and both ovaries. It is done at the same time as the hysterectomy.

• Radical trachelectomy is surgery to remove the cervix that leaves the uterus intact with pelvic lymph node dissection. It may be used for young patients who want to preserve their fertility.

For cervical cancer that has spread beyond the cervix, this procedure may be used:

• Exenteration is the removal of the uterus, vagina, lower colon, rectum, or bladder if cervical cancer has spread to these organs following radiation therapy. Exenteration is rarely required. Most commonly it is used for some patients with a recurrence of cancer after radiation treatment.

Complications or side effects from surgery vary depending on the extent of the procedure. Patients may experience significant bleeding, infection, or damage to the urinary and intestinal systems.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. Radiation therapy may be given alone, before surgery, or instead of surgery to shrink the tumor. Many women may be treated with a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy

The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation given from a machine outside the body. When radiation treatment is given using implants, it is called internal radiation therapy or brachytherapy. A radiation therapy regimen (schedule) usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time.

Side effects from radiation therapy may include fatigue, mild skin reactions, upset stomach, and loose bowel movements. Side effects of internal radiation therapy may include abdominal pain and bowel obstruction, although it is uncommon. Most side effects usually go away soon after treatment is finished. After radiation therapy, the vaginal area may lose elasticity.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by stopping the cancer cells’ ability to grow and divide.

Systemic chemotherapy gets into the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. Although chemotherapy can be given orally (by mouth), most drugs used to treat cervical cancer are given intravenously (IV). IV chemotherapy is either injected directly into a vein or through a thin tube called a catheter, which is a tube temporarily put into a large vein to make injections easier. The side effects of chemotherapy depend on the woman and the dose used, but they can include fatigue, risk of infection, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, loss of appetite, and diarrhea.